I started programming at eleven. Not because I cared about corporations, or money, or career—I wanted to build worlds. Visual stories with their own lore, their own languages, their own fashion, their own color palettes. Virtually none were realistic. That was the point.

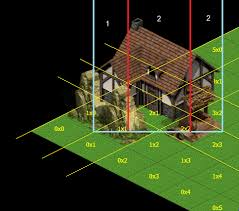

By fourteen I was building tiling map-makers, isometric engines, primitive scripting languages to animate characters through scenes I'd sketched the night before. My father refused to pay for continuous internet—we had dialup, metered by the minute—so I taught myself from books. The public library. Exclusive Books in Cavendish Square, Cape Town, where I'd convinced my mother to buy me an 800-page volume on 3D graphics programming.

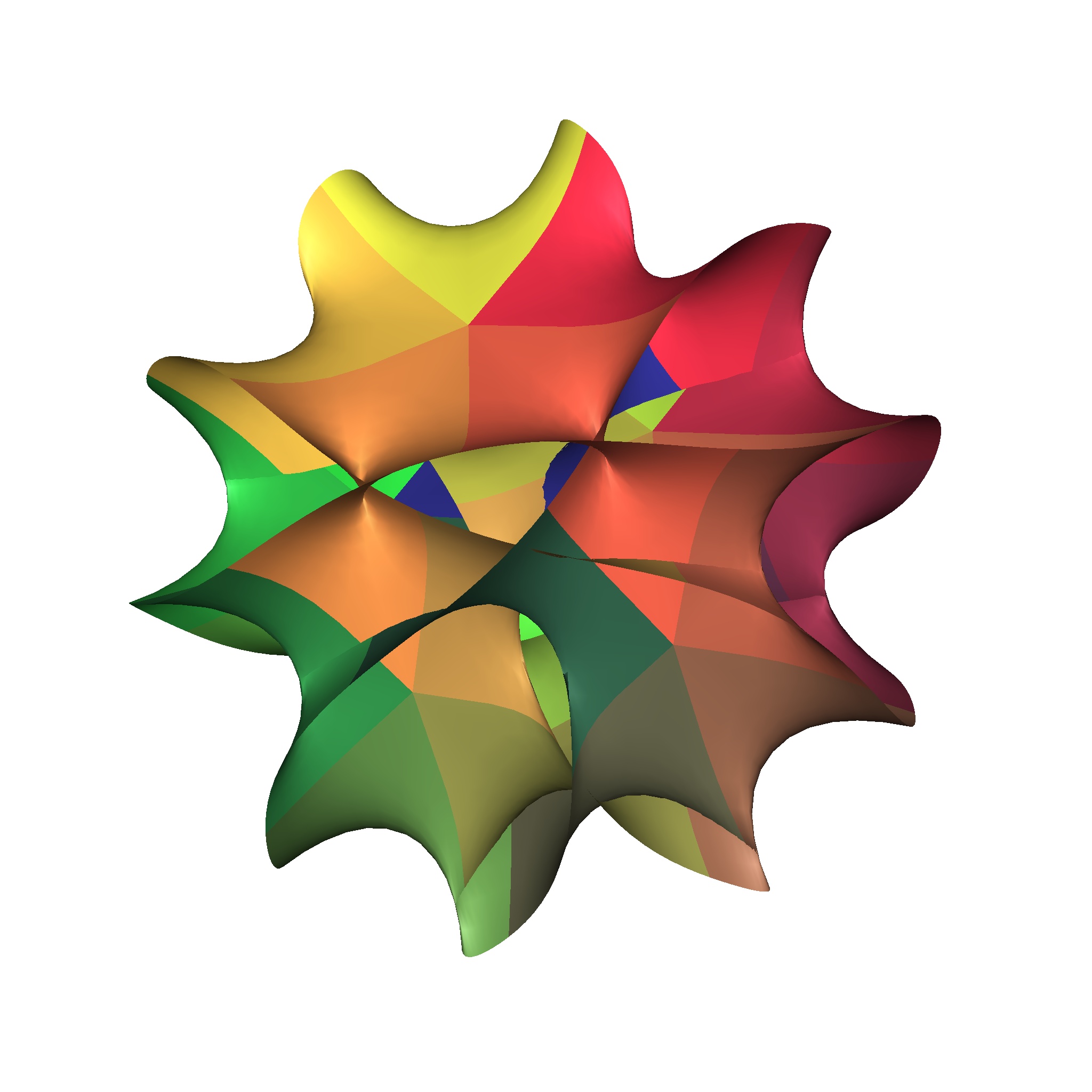

Ages 14–17. Sketches, renders, worlds that existed only on paper and in code.

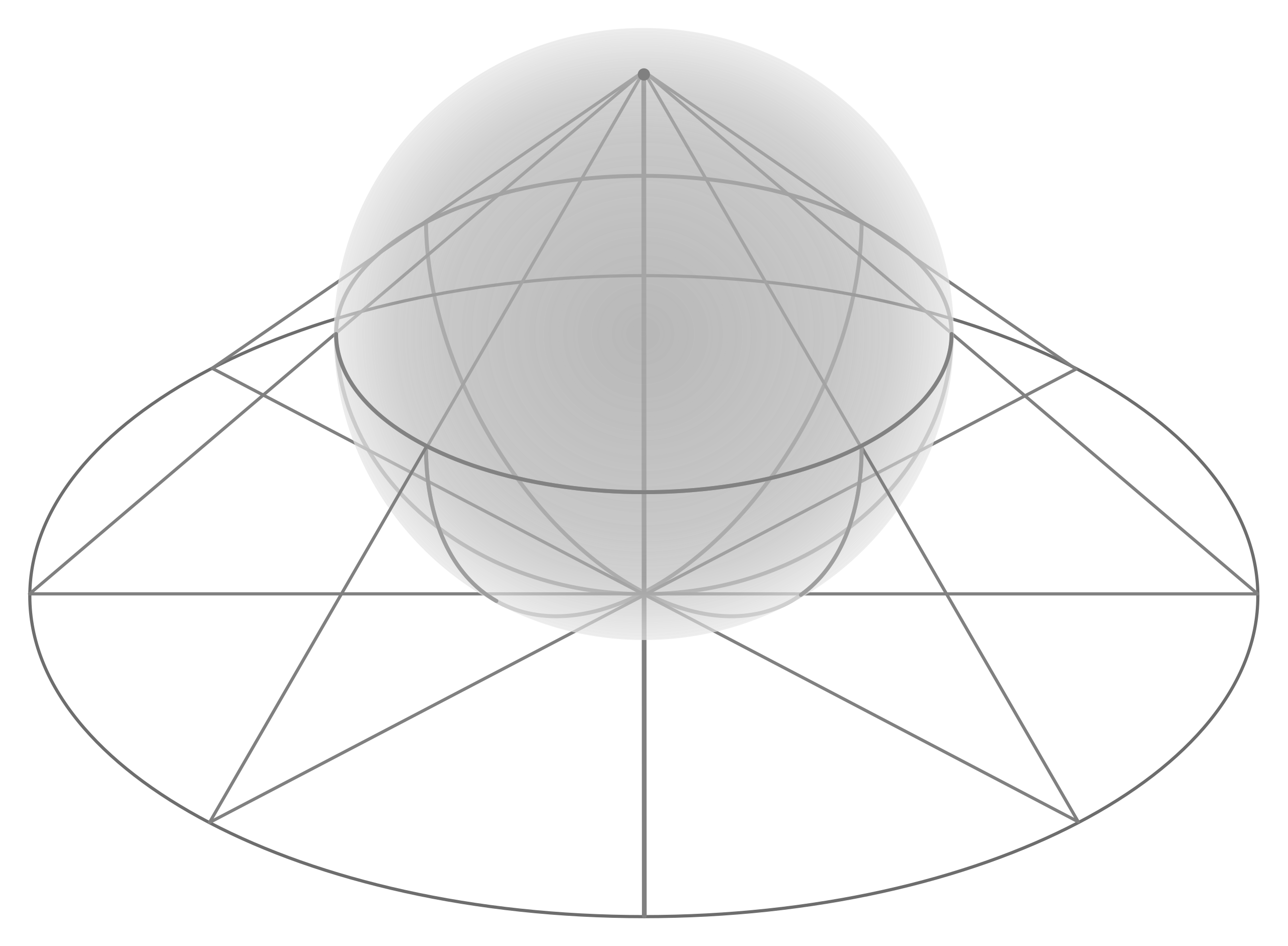

The book had a chapter on raytracing. I spent months on it. The mathematics was beautiful—not useful, beautiful. How light bounces. How surfaces reflect. How a few equations could conjure depth and shadow from nothing.

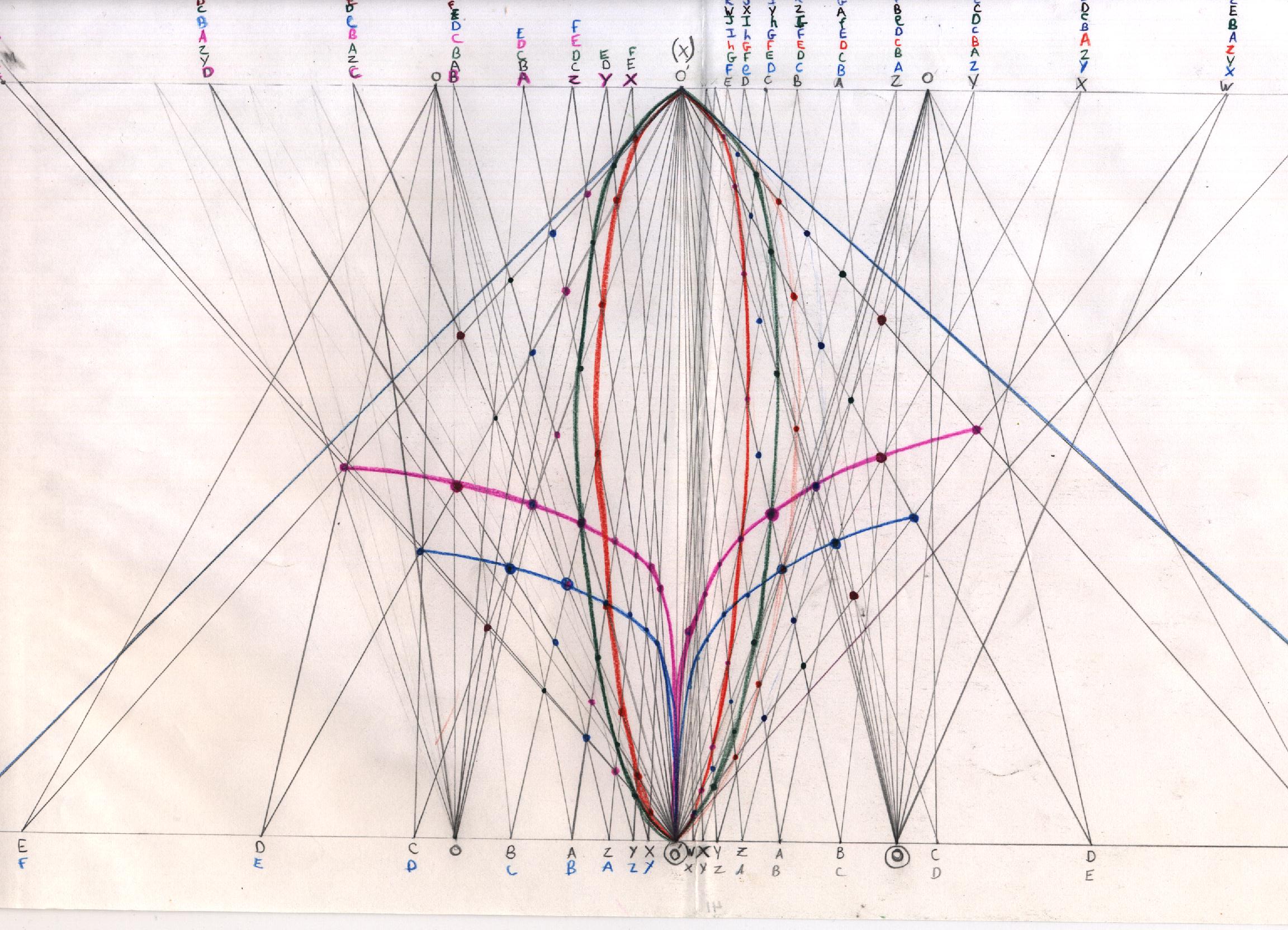

But something puzzled me. The transformation matrices had four coordinates, not three: x, y, z, w. Why? What was w? I could make it work—plug in the numbers, get the perspective correct—but I didn't understand why. The mystery nagged at me for years.

Only much later, at MIT, would I learn that the natural language for building a raytracer is projective geometry—the study of lines through the origin in higher-dimensional space. That mysterious w coordinate was a window into a playground where parallel lines meet at infinity and every transformation becomes linear. I took 18.721 Algebraic Geometry with Michael Artin and fell in love. I TA'd for him twice. The subject has given my life an infinitude of enrichment—a deep, abiding love that has never faded. And only later still would it become infinitely useful: the same geometric language describes the moduli spaces of quantum fields and strings.

I was not social during those years. I slept through classes—they moved too slowly. Raced through homework, which was mostly annoying. Then stayed up all night: sketching, illustrating, 3D modeling, programming, building engines no one would ever use for games no one would ever play. The competitions came as byproduct. Eskom Expo. ISEF. A minor planet. None of it was the goal. The goal was the worlds.

The obsession never left. It just changed medium.

I've carried a professional camera for fifteen years. Shot a short film for the 48 Hour Film Project with a crew of fifteen. Storyboarded feature films that remain unproduced. Founded Persona, an art community in New York, because I needed people around me who understood that making things beautiful was itself a form of rigor.

The auteur theory holds that a filmmaker makes the same film over and over, each work a variation on a single obsession.

The mathematics I study now—factorization algebras, the geometry of quantum field theory—I chose them for the same reason I chose raytracing at fourteen. They're beautiful. The way local structures compose into global ones. The way symmetry constrains possibility. The way a few axioms can unfold into infinite consequence.

Utility came later, almost by accident. It turns out that understanding how things compose is useful for building institutions. But that was never why I learned it.

I learned it because it was beautiful.

We shall not cease from exploration

And the end of all our exploring

Will be to arrive where we started

And know the place for the first time.

Through the unknown, unremembered gate

When the last of earth left to discover

Is that which was the beginning;

At the source of the longest river

The voice of the hidden waterfall

And the children in the apple-tree— T.S. Eliot, Little Gidding